Handel’s Messiah: A Call to Love and Justice

I have performed Handel’s Messiah three times during the past two weeks. On December 5, the London Pro Musica Choir, which I joined in September, led a lively Sign-Along Messiah in downtown London. A week later we traveled to St. Marys, a small town near Stratford, Ontario, to sing it in concert there. Then, joined by a chamber orchestra and four gifted soloists and led by Artistic Director Paul Grambo, we gave a soul-stirring performance at London’s St. James Westminster Anglican Church, where I also sing in the church choir.

Amazement

Although I’ve sung selected choruses in church choirs and joined some sing-along events in recent years, until the past two weeks I had not done complete concert performances of Messiah since my undergraduate years as a philosophy and music double major in Sioux Center, Iowa. (That’s longer ago than I care to tell or you want to know!) So I was amazed at how quickly the chorus bass lines came back, and even more amazed at how profoundly singing this music has moved me.

Perhaps I shouldn’t be surprised. I grew up hearing Handel’s Messiah performed each Advent season by the Ripon Oratorio Society in north-central California. Every year both Mom and Dad sang in this large community choir. My memoir Dog-Kissed Tears (pp. 15-17) tells how I associate “Comfort ye my people,” the opening tenor aria, with my father’s voice. So the oratorio belongs to my musical and religious heritage; hearing it stirs fond memories from childhood.

Still, I’ve had reservations about Messiah performances over the years. As an aspiring undergraduate composer, I wondered why people keep returning to such a familiar and safe composition—over 200 years old!—instead of exploring newer and more timely music. And more recently, as a social philosopher, I’ve worried that the oratorio’s elements of sentimentality (e.g., “He was despised”) and triumphalism (e.g., “Hallelujah”) can feed into a toxic brew of false resentment and authoritarian hatred in MAGA America.

What amazes me, then, is how singing this music in a new community with an outstanding conductor and first-rate musicians has overcome my reservations. I’m not only amazed but grateful. For just a year ago, as my post on Morten Lauridsen’s “O Nata Lux” describes, I struggled to sing any music that expressed hope amid sorrow.

Messiah’s Story

Portrait of George Frideric Handel by Thomas Hudson (1749). Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

This experience leads me to ponder the structure and meaning of Handel’s well-known work. The oratorio’s librettist was Charles Jennens (1700-1773), a wealthy landowner who had literary and musical interests. In 1741 he compiled a diverse array of biblical texts into three parts, each of them subdivided into several scenes. Then he asked George Frideric Handel (1685-1759) to set the texts to music, which Handel accomplished in less than a month. The texts largely stem from the Psalms, Isaiah, the Gospels, I Corinthians, and Revelation. Jennens arranged them to tell a complete story about the need and promise, birth and life, death and resurrection, and the ascension and ever-expanding reign of Jesus, the anointed one (which is what the Hebrew Messiah and Greek Christ actually mean).

Portrait of Charles Jennens painted by Thomas Hudson (ca. 1745). Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

It’s clear Jennens wanted to emphasize the Messiah’s divinity and thereby challenge the Deists of his day. Deists downplayed this and denied divine intervention in human affairs. Yet the most affecting moments in the score are ones that stress the Messiah’s humanity. And that makes me think the official structure and meaning Jennens provides need not be what we contemporary choristers and audiences experience.

I won’t lay out the official narrative. It’s easy enough to decipher from the score, and the Wikipedia article “Structure of Handel’s Messiah” maps it well. Instead, let me share how I’ve experienced it in recent days. Although Pro Musica did not present the entire oratorio—just Part One and a few selections from Parts Two and Three—we did sing enough of it that the ebb and flow of each part came through. Let me focus on Part One, often called the Christmas section. (I might talk about Part Two or Three in a subsequent post.)

Expectation and Surprise

Part One begins with a short “Sinfony” or Overture and later includes a “Pifa” or Pastoral Symphony. These are the only purely instrumental pieces in the entire oratorio. We know the librettist intensely disliked the opening “Sinfony.” I expect Jennens wanted something more majestic, something less self-effacing. But I think it is just right. Without bombast, it sets up an expectation of what’s to follow and brings us to the opening call of “Comfort ye my people” (tenor recitative)

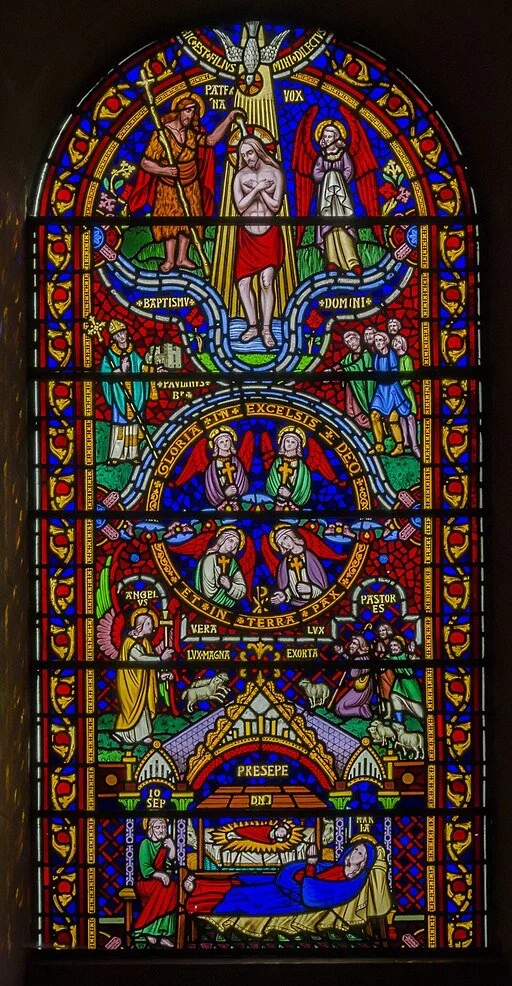

Southwell Minster stained-glass window by O'Connor, 1851. Image by Jules & Jenny from Lincoln, UK, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

That call becomes the first big surprise of this score. For the call of comfort carries through the subsequent fireworks of “Every valley shall be exalted” (tenor air) plus “And the glory of the Lord” (chorus); the foreboding of “Thus saith the Lord” (bass recitative) and “But who may abide the day of his coming?” (alto air); the vigorous cleansing of “And he shall purify” (chorus); the magical sequence from a virgin conceiving (alto recitative) through good tidings to Zion (alto + chorus) and the people in darkness seeing a great light (bass recitative and air) to the untrammeled joy of “For unto us a child is born” (chorus). It carries through to the instrumental Pifa that recalls gentle shepherd pipes and introduces Luke’s words about sheep herders at night (soprano recitatives) hearing angels burst out: “Glory to God … and peace on earth …” (chorus).

Miren Aire, Basque shepherd. Photo by Dani Blanco (Argia aldizkarian), CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

What leads the daughter of Zion to “Rejoice greatly…” (soprano air)? It’s the humble healing the Messiah brings, not the exalted glory previous choruses suggested: the blind and deaf and lame and mute receive care (alto recitative); the lambs are gathered up, and the weary find rest (alto and soprano duet). Then Part One concludes with “His yoke is easy” (chorus), a bouncing celebration of this caregiving Messiah. Comfort ye my people.

So Part One sets up an expectation of earth-shaking transformation—valleys exalted, rough places made plain, and everyone seeing the glory of God. But then it surprises us with how tender this transformation is. That’s the promise of Emmanuel, of God with us. It’s a promise not of almighty power but of concrete love and justice. As my friend Arnold De Graaff shows in his recent book, that’s indeed how one should read the entire Hebrew Bible, which Messiah frequently quotes: as The Prophetic Call to Love and Justice (Wipf and Stock, 2025).

Humble Healing

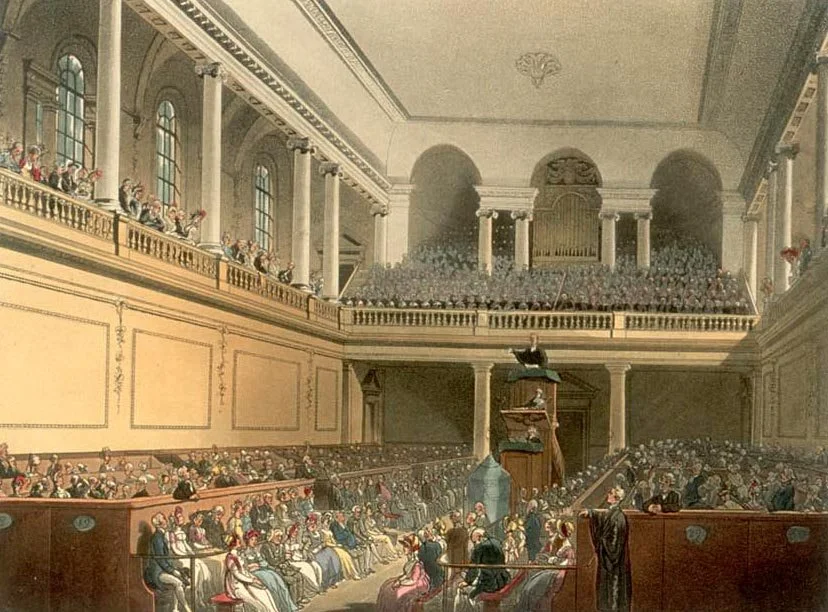

I don’t know whether that’s the story the librettist intended. But it’s one singers and audiences can experience today. And it could well be one Handel himself wanted to bring out. For he was a generous patron of charitable causes. The first ever performance of Messiah—in Dublin, Ireland on April 13, 1742 with Handel conducting—was a benefit concert. The proceeds helped two hospitals for the desperately poor and secured the release of 142 indebted prisoners.

Chapel of the Foundling Hospital, London, where Handel’s Messiah was performed. From an engraving with multiple sources. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Moreover, from 1750 until Handel’s death in 1759, he and his student J. C. Smith led annual charity performances of Messiah to benefit London’s Foundling Hospital, a home and health care center for neglected and orphaned children. Handel became a governor of the hospital, and he bequeathed it a manuscript copy of Messiah upon his death.

So hearing Part One as an ode to the humble healing of humanity can ring true to Handel’s own experience as well as our own.

Many people believe King George II stood for Part Two’s Hallelujah chorus at the 1743 London premier of Messiah, obliging everyone else to stand as well. And that’s why people stand up for this chorus even today. But this is a legend, and there’s no solid evidence the king ever attended a Messiah performance. Nor do I think the Hallelujah chorus is the high point it’s often taken to be.

Stained-glass window depicting the Adoration of the Shepherds, created by the studio of F. X. Zettler and installed in Springboro, Ohio. Photo by Nheyob, CC BY 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Given the surprise Handel so masterfully orchestrates in Part One, perhaps it’s time for a new custom. Listen to the three-minute linked performance by the National Youth Choir of Great Britain (be sure to watch to the very end!), and then consider this: After the playfully animated counterpoint of “His yoke is easy” gives way to the final solemn chords of “and his burthen is light,” perhaps all of us, musicians and listeners alike, should pause in silence. Like the shepherds of many a Christmas card and crèche, we should kneel in quiet adoration of the humble healer, the one who calls us to love and justice, the Prince of Peace.

Note: This is my last post for 2025. Thank you for reading my periodic attempts to shine a little light in the darkness. I wish all of my readers a blessed New Year!