Rejecting White Christian Racism

False White Gospel

Jim Wallis. Photo credit: JP Keenan/Sojourners

Recently, Jim Wallis came to West Michigan to help launch his new book The False White Gospel (St. Martin’s Essentials, 2024). As the book’s subtitle indicates, Wallis urges his readers to reject white Christian nationalism, reclaim true faith, and rekindle American democracy. The book resonates deeply with the writings of Kristin Kobes Du Mez and David Gushee discussed in Saving Democracy from Its Evangelical Foes, my previous post. Wallis issues a clarion call for what I describe there as “personal-political conversion.”

I didn’t hear Wallis speak: a nasty head cold kept me at home. I was able to buy and read his new book, however, and I’d like to talk about it here.

Jim Wallis is well known among American evangelicals. In the early 1970s he helped write The Chicago Declaration of Evangelical Social Concern (1973), which his new book reprints (pp. 28-29). Around the same time, he co-founded the intentional Sojourners community in Washington, DC and served as founding editor of Sojourners magazine, a progressive voice on faith and politics. More recently he became the inaugural holder of the Archbishop Desmond Tutu Chair in Faith and Justice at Georgetown University and the director of its Center on Faith and Justice. His new book draws generously from many decades of reflection and activism as a leading evangelical spokesperson for faith-filled Christian politics.

Bonhoeffer Moment

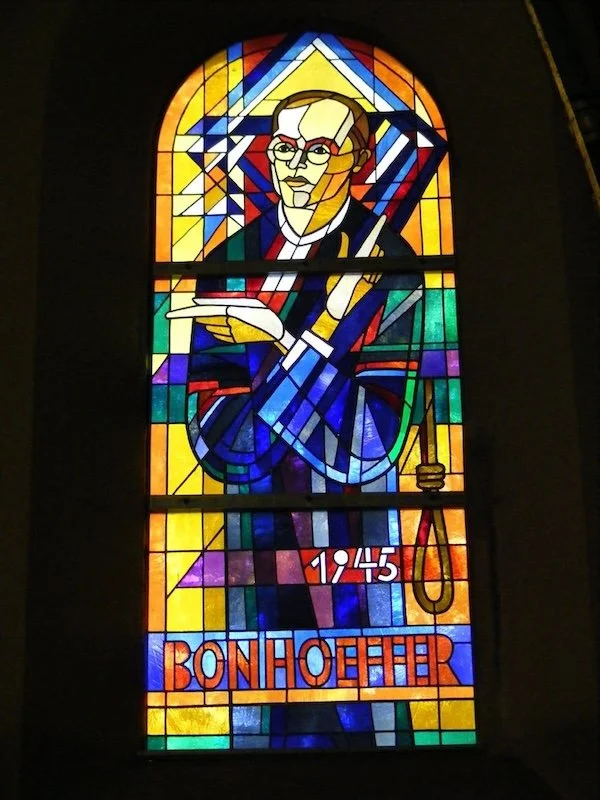

Dietrich Bonhoeffer stained-glass window, Johannes-Basilika, Berlin. Photo by Sludge G, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Wallis does not mince words. For Christians in the United States, today is what he calls a “Bonhoeffer moment” (p. 3). As a young pastor in Germany, Dietrich Bonhoeffer helped lead protestant pastors who resisted the rise of Nazism in the 1930s. This “confessing church” (bekennende Kirche) unflinchingly opposed the embrace of Hitler and his henchmen by many fellow protestants led by the so-called “German Christians” (Deutsche Christen). The Theological Declaration of Barmen (1934)—now included in the Book of Confessions of the Presbyterian Church (USA), to which I belong—provides the theological basis for their opposition. Bonhoeffer did not survive World War Two: the Nazis hanged him in a concentration camp shortly before the war ended. But his courageous witness continues to inspire those who refuse to sell out their faith for the sake of political power.

Today American Christians are in a similar crisis, Wallis says, and they too must choose: “We are literally in a battle now between false religion and true faith and between racial fascism and multicultural democracy. … Democracy, faith, and the generational future of our faith communities are all at stake. If communities of faith today won’t fight for a multiracial democracy in this country, both will fail” (p. 5).

Multiracial Democracy

Two things in particular strike me about Wallis’s book. First, more than many others who oppose what David Gushee calls authoritarian reactionary Christian politics, Wallis emphasizes the central role of racism in what he calls “white Christian Trumpism” (pp. 25-26). Second, he also does not hesitate to label the beliefs and practices of white nationalist evangelicals a “false religion”: they live out of what his book title calls a “false white gospel.” Accordingly, Wallis devotes his book to re-reading six central passages from the Hebrew Bible and Christian New Testament. And he lays out a case for American Christians to join hands with other citizens in working toward a genuinely multiracial democracy.

What Wallis shows, in my own terms, is that a traditional religion like Christianity does not need to stand on the wrong side of history, even though it often has. When revitalized from within, it can inspire its adherents both to resist forces of injustice and oppression and to forge new pathways for justice and freedom. This is a helpful and hopeful reminder, especially for those of us who have long since given up on that “old time religion” or perhaps never felt its attraction in the first place.

Repenting of Racism

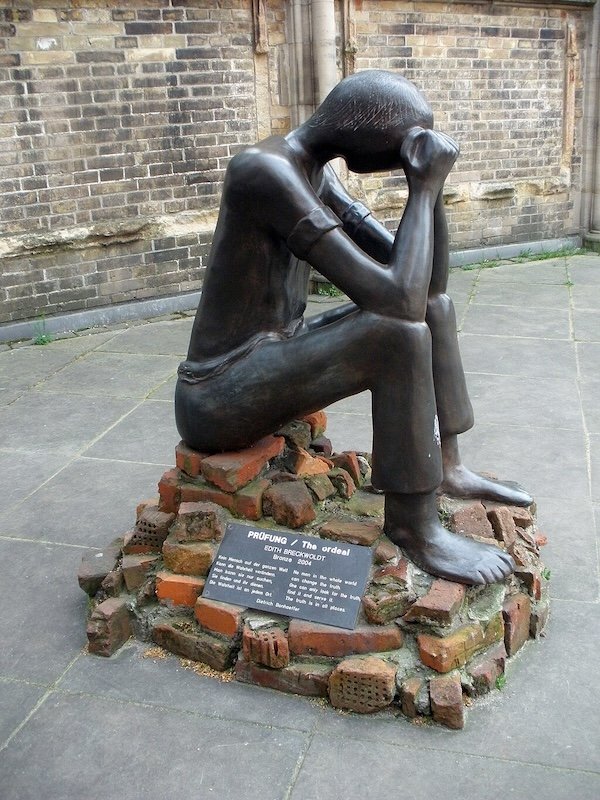

Prüfung (The Ordeal). Bronze sculpture by Edith Breckwoldt (2004) at St. Nicholas' Church, Hamburg, Germany, in memory of prisoners from the Sandbostel concentration camp. The placard text, attributed to Dietrich Bonhoeffer, reads: No man in the whole world can change the truth. One can only look for the truth, find it, and serve it. The truth is in all places. Photo by Emma7stern, CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Wallis also shows that there’s no way forward for political democracy in the United States unless white Christians “repent, repair, and redeem America’s original sin for white people” (p. 11), namely, white supremacy and systemic racism. From the colonies through the Civil War to twentieth-century segregation and contemporary voter suppression, white Christians have destroyed Indigenous peoples, exploited enslaved Africans, and rejected the rights of people who do not look or act like them. There’ve been exceptions, of course, and gradually white Christians in the United States have learned to embrace rather than fight their neighbors. Yet there are many personal and structural changes to accomplish before white Christians really do find appropriate places in a multiracial democracy.

That’s what makes the current moment so crucial. Too many white evangelicals, when they hear the slogan “Make America Great Again,” think, Yes, let’s go back to the days when white Christians both literally and figuratively called the shots. But those MAGA days are gone—gone for good, I’d say—and they weren’t so great to begin with, especially not for anyone who received the shots called.

Photo by Seval Torun on Unsplash

Yet there is one place white Christians do need to revisit. As Wallis shows, they need to return to the genuine sources of their own religion, a religion of love and not hatred, of service and not domination, of earth keeping and not exploitation. They can find such sources speaking from the biblical texts that evangelicals hold sacred. But, in the words of Jesus (Matthew 13:1-23), the question is this: Do they—or do we—have ears to hear?

Note: If you wish to receive notices of my blog posts in the future, please email me using the contact link on this website.